98-Year-Old Betty Lindberg: From Telegraph Key to Smartphone and Still Eyeing the Future

The name of the landmark study: "Exercise and Immunity in

the Elderly." The year: 1991. Betty Lindberg had recently turned 66.

"Your results have been the high point of the

investigation," wrote one of the Appalachian State University researchers in a

follow-up letter informing Betty that she had the cardiovascular fitness of a

42-year-old. "You are, indeed, an

inspiration to all of us."

The name of the class is "Senior Fit." The year is 2023.

Betty Lindberg is 98.

As the group gathers one January morning at LA Fitness in

Buckhead, Betty fetches a resistance band and exercise ball and lines up in the

back row. It's her favorite spot, she explained; from there, she can see what

everyone else is doing even when she can't hear the instructor over "Jolene"

and "Dance, Dance, Dance." Plus, she said, she feels self-conscious in the

front.

Wielding five-pound weights in each hand, Betty proceeds to

smoke most of the class.

On the way out, a few of the regulars say goodbye. "Take it

easy," says one offhandedly to Betty.

"Why?" asks Betty.

Yes, Betty Lindberg was already old enough three decades ago

to qualify as "elderly." Yes, the longtime member of Atlanta Track Club still

works out six days a week - Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays at her exercise

class ("I wish it were tougher") and Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays with a 2.5-mile

run/walk around her neighborhood. She takes Saturdays off to get her hair done.

Yes, she has participated in every Atlanta Journal-Constitution Peachtree Road

Race but one since 1989, with a shelf full of finish-line photos in her

pine-paneled den to prove it.

Yes, she is returning to compete in the USATF 5 km

Championships, to be contested as part of the Publix Atlanta Marathon Weekend

5K this Saturday morning. So, if you want to run in the footsteps of the woman

who last year made the pages of Sports Illustrated for setting an age-group

world record here - her time of 55:48 obliterated the previous mark by more

than 30 minutes - this is your chance. Registration

is still open.

"Probably no world record this

time, but I will be the only woman 95-99 giving it a try!" she reported last

week in an email update.

And yes, we are referring to her by her first name rather

than last. Trust us, we are not being patronizing to this woman in her 10th

decade who still carries her own groceries out to the car before driving home with

confidence, then shouts out questions at the TV while watching "Jeopardy!"

after replying to emails on her iPhone 11.

Rather, it's an acknowledgement that when all of Atlanta

knows the woman with the motto of "keep moving" as simply Betty, you go with

the flow.

Which is pretty much following the example of what Betty has

done all her life. Over a takeout post-workout lunch of Brunswick stew, fried

okra and collard greens in her tidy dining room, Betty and her two children,

son Craig and daughter Kerry McBrayer, share family stories, photos and

memorabilia, even breaking into song. Lunch turns into coffee, and still there

are tales to be told, laughs to be laughed, heads to be shaken at their

modest-yet-indomitable matriarch. Examples: When she shattered the 5K record,

she hadn't even told her kids she was going after it; when she ran the

Resolution Run less than a month after getting a hip replaced about 10 years ago,

she neglected to alert them.

Both retired now, Betty's kids both know how precious it is

to not only still have their mom, but to have one who just

got home from the gym.

"We're really making the most of it," said Kerry. "This is

the time. Now."

***

In 1924 - with a Model T selling for $265 and Calvin

Coolidge as president - Betty Ann Reynolds was born in the tiny

Finnish-American village of New York Mills, Minnesota, to Clyde and Henna

(Hopponen) Reynolds.

When she was 2 years old, the family moved to nearby Parkers

Prairie, where her father worked in a lumber yard before taking over a bar and

restaurant; her grandparents ran a bar and restaurant, too, over in New York

Mills. There, Betty ate so much ice cream as a girl that she doesn't care for

it much anymore, and her older brother - who would go on to earn a Ph.D. in

theater and speech - would be hoisted onto the bar by grandpa to serenade

customers with ditties such as "I'm a villain, a dirty little villain, I leave

a trail of woe where'er I go …". " (Yes, she still knows all the lyrics.)

As a child, Betty played dolls and jacks with her

girlfriends, made mud pies with eggs from her grandmother's Bantam hens, and

enjoyed packing a sandwich and dessert into a little pail to go picnicking on the

lawns of neighbors. "You didn't take part in any sports!" she told podcaster

Ali Feller last year. "Girls just sat and watched the boys play."

She hunted pheasant and duck, though, and went ice fishing,

eating the bounty. She and her brother liked to sit around the family's big

radio and listen to adventure stories, and she remembers Robert, four years

older than she, holding tight to her hand one day so she wouldn't blow away as

they walked home from school in a blizzard.

When Betty was a sophomore, her family moved back to New

York Mills, where she graduated from high school in 1942. She thought she would

become an English teacher, but as part of the war effort went to work for the

National Youth Administration, where she had the option of learning how to work

with sheet metal to build airplanes or how to construct radios and install them

in airplanes going off to war. She chose radios and was lucky enough to get an

instructor who also taught Morse Code (yes, she still remembers it, snappily

typing out "Peachtree" on an old telegraph key brought out by her daughter.)

Instead of going to work in a factory, however, Betty took a

job as a radio telegraph operator with Northwest Airlines. From the ground, she

communicated with pilots of the DC3s - noting ETAs on a chalkboard - and used

Morse Code

to send and receive information

for flight reservations. After stints in Minneapolis and Chicago,

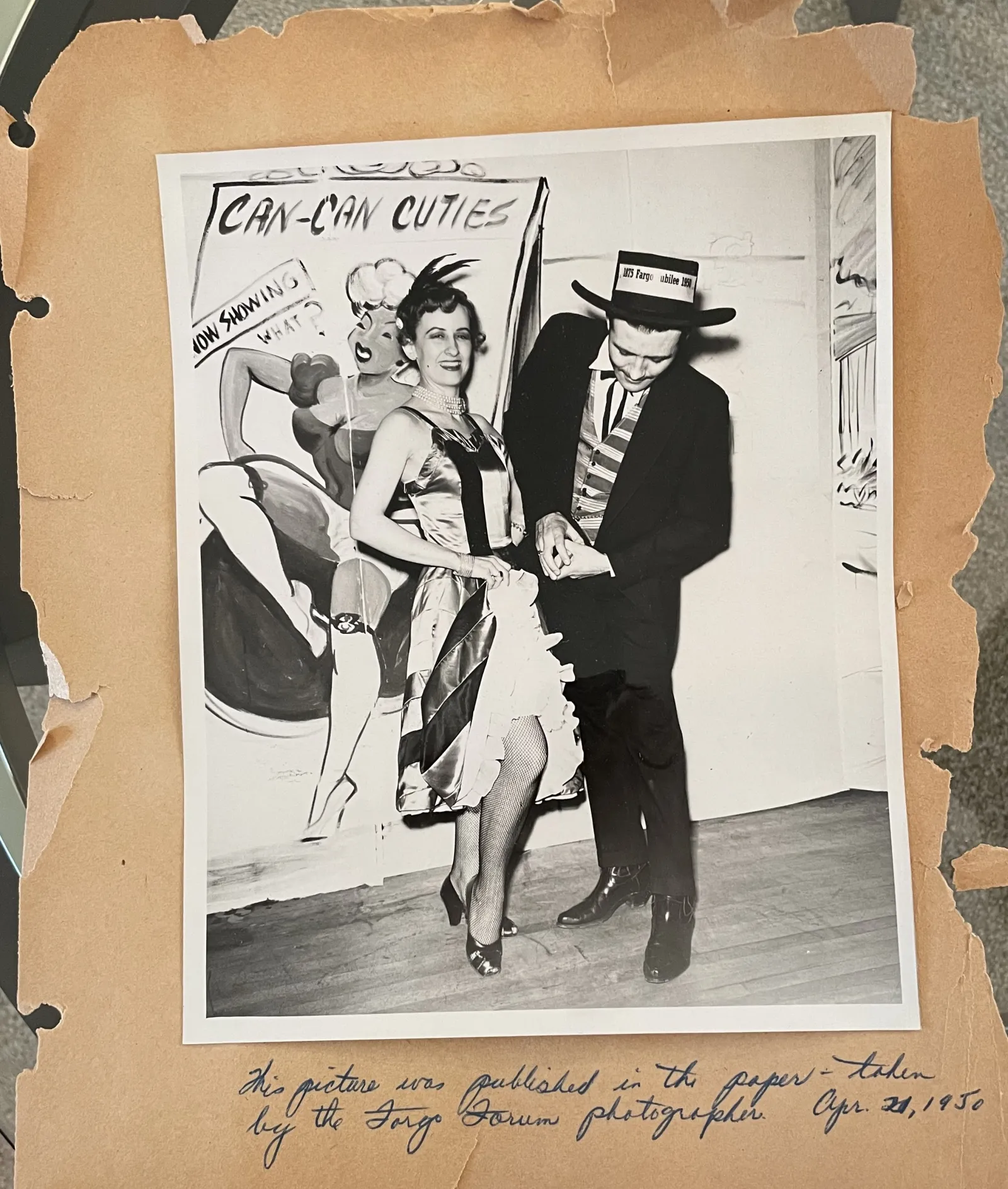

she transferred to Fargo, N.D., where she impressed a tall Navy aviation veteran

from the city ticket office with her speed on the telegraph. He took a special

trip out to the airport one day just to find out who exactly this Betty

Reynolds was.

Not long after, the two met again on an office hayride. "We

talked and we talked and we talked and we talked," Betty remembers.

"I think mom's comment has been that when she laid eyes on

him, he didn't stand a chance," said her daughter.

Betty Ann Reynolds and H.O. (Lindy) Lindberg were married in

1948. By the time Kerry came along in 1951, Betty had quit her job; a few years

later Lindy was transferred to Bloomington, Minnesota, where son Craig was born

in 1956. A year or so later, the toddler was standing on the front seat next to

Betty on the way back from a doctor's appointment when, in those pre-carseat

days, "I go whipping around a corner and he flies out the door and lands in a

snowbank," she recalled. "That's as safe as I kept my kids."

In 1958, the family moved to Atlanta as Northwest launched

service in the city; she still lives in the cozy house they bought a few years

later. (Asked how long it took her to get used to the heat and humidity, Betty

replied: "I'm still working on it.") Lindy's office was in the just-completed

Lenox Square shopping center, which years later would become the site of the

Peachtree start line.

Lindy's new job in Atlanta meant more travel opportunities,

and the walls of their home were soon lined with art and souvenirs from their

many trips to Asia. On one trip to China in the 1980s, the couple missed a boat

to travel down the Yangstze River, and when their hired car got a flat tire the

driver had to unload all of their luggage to reach the spare. Betty remembers

standing on the side of the road, with hundreds of locals looking on.

"They might never have seen a Westerner before," she said.

As the kids got a little older, Betty took a job at Lenox

Square, too - in customer service at Rich's, a department-store chain

headquartered in Atlanta. (She retired in 1992.) A leader for her children's

Brownie, Cub Scout and Girl Scout troops, PTA president, on the council of

Peachtree Road Lutheran Church, their mom "just wasn't a sit-at-home kind of

person," said Kerry.

But while she may have spent a lot of time running around,

she didn't start running in the literal sense until she was 63 years old.

It was 1988 when Kerry asked her parents if they would meet

her and her husband at the Peachtree finish line to take them back to their car

at the start.

"I had no idea what a road race was," said Betty. "Why are

people getting up at the crack of dawn on the Fourth of July?" When she saw the

mass of runners smiling and waving as the approached the finish, though, "I

said, 'I can do that; that looks like fun.'"

And then - because when Betty says she's going to do

something, she does it - she did it.

She soon discovered that running required a bit more

exertion than her only previous foray into working out: the passive vibrating

exercise belt, for which an ad at the time exclaimed: "What! I can exercise

without effort? YES!" Betty's first-ever run, with Lindy in their hilly

neighborhood, lasted about 2/10th of a mile by her recollection

before it ended with a gasp that it was time to go home.

Betty kept at it; Lindy less so. At a solid 6'2" a foot

taller than his wife, he found running too punishing. Instead, he turned to faithfully

volunteering at Betty's races, translating at the Peachtree for any

Scandinavian elite distance runners who travelled to the world-renowned race

and helping collect the old tear-off bib tags at the finish line. Back then, the

race timed only the first 1,000 runners; after that he would leave to find

Betty. He also volunteered at the 1996 Olympic Games, as did Betty and son

Craig.

In 1989, a year after she discovered Peachtree, Betty ran

her first. (The next day, a sales manager asked her where she had purchased the

T-shirt on her desk. "I earned that!" she recalls informing him.) Soon, she

became a Peachtree volunteer as well as participant, holding the barrier for

her wave before tossing off her volunteer shirt and jumping in. In 2019, for

the 50th Peachtree, she served as an honorary starter before joining

the celebration as it made its way to Piedmont Park.

She has done every Peachtree since, missing only 2005 when

she was caring for Lindy as he battled Parkinson's. The disease's progression,

said Kerry, was one of the few things to ever visibly upset her mother. Lindy died

in January of 2006.

In the early years, Betty started the race with Kerry and

her husband but then shooed them ahead so they could run their own, faster pace.

Last year on July 4, Betty drove herself to the start line, parking in her

church lot before meeting up with son Craig and his family. They all stopped at

a table around Mile 1 set up by granddaughter Nicole, where the cheering

section enjoyed breakfast casserole, fruit salad and mimosas. (Yes, Betty had a

sip). As the entourage carried on after grabbing a quick family photo, Betty

slapped high fives and obliged selfie requests as Craig and his wife Cyndi,

along with Betty's grandsons Eric and Kyle and their wives Lilly and Jackie, acted

as wingmen to shield her from admirers when necessary.

After crossing the finish line, Betty declared that she had

just completed her last Peachtree.

"Every year when she finishes, she says 'I'm never doing

this again,'" said Kerry over lunch.

"Absolutely not. I will not sign up for it. No, I will not,"

said Betty.

Kerry and Craig exchange skeptical glances.

Peachtree or no Peachtree, Betty still sees racing in her

future. Seven years after setting her first age-group world record at 800

meters (6:57.56), she already has her eye on records in the 100-105 age group.

(Yes, she knows what they are.)

"I looked up the 100, 200, 400, 800 and 1500, and I am

pretty sure I can beat them," she says. "But I don't know, maybe somebody will

come along who can do it better than I can."

Said Craig: "Let's just see 'em try."